Chapter 5.1. Alias Analysis

Alias analysis involves determining if two identifiers point to the same memory allocation. The task is challenging, with various options that balance precision and cost, including flow sensitivity, field sensitivity, and path sensitivity. In general, there are two main approaches to analysis: the lattice-based approach and the meet-over-all-paths (MOP) approach.

5.1.1 Alias Analysis Trait

RAPx provides the AliasAnalysis trait for alias analysis. The trait has several methods, which enables users to query the aliases among the arguments and return value of a function based on the function DefId, or the aliases of all functions as a FxHashMap. Developers can implement the trait based on their needs.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub trait AliasAnalysis: Analysis { fn get_fn_alias(&self, def_id: DefId) -> Option<FnAliasPairs>; fn get_all_fn_alias(&self) -> FnAliasMap; fn get_local_fn_alias(&self) -> FnAliasMap; } }

The alias analysis result for each function is stored as the FnAliasPairs type, which contains a HashSet of multiple alias relationships, and each alias relationship is recorded as AliasPair.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub struct FnAliasPairs { arg_size: usize, alias_set: HashSet<AliasPair>, } pub struct AliasPair { pub left_local: usize, // parameter id; the id of return value is `0`; pub lhs_fields: Vec<usize>, // field-sensive: sequence of (sub) field numbers for left_local pub right_local: usize, // parameter id, which is an alias of left_local pub rhs_fields: Vec<usize>, // field-sensive: sequence of (sub) field numbers for right_local } }

RAPx has implemented a default alias analysis algorithm based on MOP.

5.1.2 Default Alias Analysis

The MOP-based alias approach is achieved via a struct AliasAnalyzer, which implements the AliasAnalysis trait. The detailed implementation can be found in mop.rs.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub struct AliasAnalyzer<'tcx> { pub tcx: TyCtxt<'tcx>, pub fn_map: FxHashMap<DefId, MopFnAliasPairs>, } }

The results can be retrieved by decoding the data structure of FnAliasPairs .

Suposing the task is to analyze the alias relationship among the return values and the arguments, the approach performs alias analysis for each execution path of a target function and merges the results from different paths into a final result. When encountering function calls, it recursively analyzes the callees until all dependencies are resolved. This approach is path-sensitive and field-sensitive but context-insensitive.

5.1.2.1 Feature: Path Sensitive with Light Reachability Constraints

In the following code, there are two conditional branches. If adopting a lattice-based approach, a could be an alias of either x or y at program point ①. Consequently, the return value could also be an alias of either x or y.

However, this analysis is inaccurate, and a cannot be an alias of y in this program.

In fact, the function foo has four execution paths induced by the two conditional branches. Among them, only one path involves an alias relationship between the return value and y. This path requires choice to be Selector::Second in the first conditional statement and Selector::First in the second conditional statement, which is impossible. Therefore, this path is unreachable, and a should not be considered an alias of y in this program.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { enum Selector { First, Second, } fn foo<'a>(x: &'a i32, y: &'a i32, choice: Selector) -> &'a i32 { let a = match choice { Selector::First => x, Selector::Second => y, }; // program point ①. match choice { Selector::First => a, Selector::Second => x, } } }

Our MOP-based approach can address this issue by explicitly extracting each execution path and justifying its reachability through the maintenance of a set of constant constraints.

We use the following MIR code for illustration, which corresponds to the previous source code. In bb0, there is a SwitchInt() instruction that branches control flow to bb3 if _5 is 0, to bb1 if _5 is 1, or to bb2 otherwise.

Accordingly, we impose constant constraints on _5 along each branch: in bb3, _5 is constrained to be 0; in bb1, _5 is constrained to be 1; and in bb2, _5 is constrained to be neither 0 nor 1. With these constraints in place, when execution reaches the second conditional statement in bb4, the analysis can rule out two unreachable combinations of branch conditions.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn foo(_1: &i32, _2: &i32, _3: Selector) -> &i32 { bb0: { StorageLive(_4); _5 = discriminant(_3); switchInt(move _5) -> [0: bb3, 1: bb1, otherwise: bb2]; } bb1: { _4 = _2; goto -> bb4; } bb2: { unreachable; } bb3: { _4 = _1; goto -> bb4; } bb4: { _6 = discriminant(_3); switchInt(move _6) -> [0: bb6, 1: bb5, otherwise: bb2]; } bb5: { _0 = _1; goto -> bb7; } bb6: { _0 = _4; goto -> bb7; } bb7: { StorageDead(_4); return; } } }

5.1.2.2 SCC Handling

A major challenge for path-sensitive analysis lies in the presence of strongly connected components (SCCs), since loops may induce an unbounded number of execution paths. We address this challenge based on the following two observations:

- Each SCC in MIR has a dominator, i.e., every loop in MIR is a natural loop. This property allows us to construct SCC trees that capture the hierarchical structure of loops.

- Traversing the same loop path once or multiple times does not change the resulting alias relationships.

Based on these observations, we can soundly bound path exploration by collapsing repetitive loop traversals. In the following, we use a concrete example to demonstrate how these findings enable efficient and precise path enumeration in the presence of loops.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { enum Selector { First, Second, } // Expected alias analysis result: (0, 1) (0, 2) fn foo(x: *mut i32, y: *mut i32, choice: Selector) -> *mut i32 { let mut r = x; let mut q = x; unsafe { while *r > 0 { let mut p = match choice { Selector::First => y, Selector::Second => x, }; loop { r = q; q = match choice { Selector::First => x, Selector::Second => p, }; *q -= 1; if *r <= 1 { break; } q = y; } if *r == 0 { break; } } } r } }

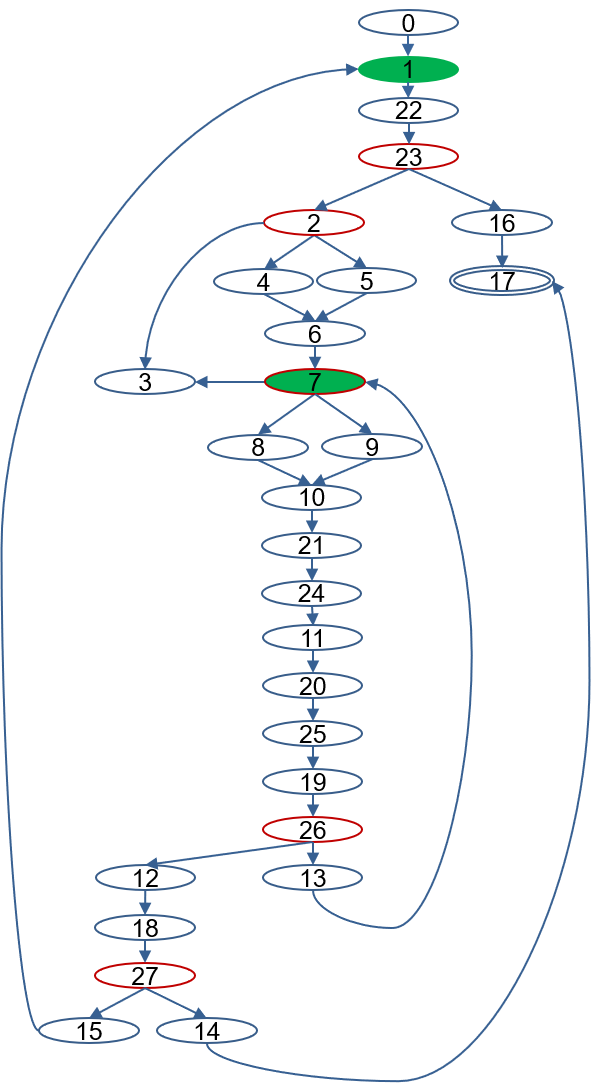

The following figure illustrates the control-flow graph of the code.

There is a large SCC

{1, 22, 23, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 21, 24, 11, 20, 25, 19, 26, 13, 12, 18, 27, 15},

whose dominator is node 1, since every path from the entry node to any node in this SCC must pass through 1.

Next, we identify sub-SCCs by removing the dominator of the SCC. Starting from node 22, which is a successor of the removed dominator 1, we discover a sub-SCC

{7, 8, 9, 10, 21, 24, 11, 20, 25, 19, 26, 13},

with dominator 7.

These two dominators form a hierarchical relationship. In practice, an SCC may contain multiple sub-SCCs, and sub-SCCs may themselves contain further nested SCCs. This naturally yields a tree structure that represents multi-level SCC nesting.

In this way, we enumerate valuable paths of an SCC tree in a recursive manner. We define a path as a sequence from the dominator to an exit of the corresponding sub-SCC. For example, 7-8-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-26 is such a path.

A node sequence is worth further exploration only if the most recent traversal between two occurrences of the same dominator introduces at least one previously unvisited node. For instance,

7-8-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-13-7-8-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-13-7 is not worth exploring, since the second segment is a duplication of the first and does not introduce any new nodes.

In contrast, 7-8-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-13-7-9-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-13-7 is worth exploring because the second segment introduces a new node 9, which may lead to new alias relationships. The resulting path is

7-8-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-13-7-9-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-13-7-8-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-26.

Using this strategy, our approach generates the following 10 paths for the inner SCC.

7-8-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-267-9-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-267-8-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-13-7-8-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-267-8-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-13-7-9-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-267-9-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-13-7-8-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-267-9-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-13-7-9-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-267-8-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-13-7-9-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-13-7-8-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-267-8-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-13-7-9-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-13-7-9-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-267-9-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-13-7-8-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-13-7-8-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-267-9-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-13-7-8-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-13-7-9-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-26

Note that this path enumeration strategy can effectively detect the alias relationship between r and y, for example via the path 7-9-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-13-7-9-10-21-24-11-20-25-19-26.

In contrast, a straightforward DFS-based traversal fails to detect this alias relationship.

Our analysis adopts a recursive strategy instead of an iterative bottom-up approach. A purely bottom-up method, although potentially more efficient, ignores path constraints introduced outside an SCC and may therefore over-approximate reachable paths. To address this limitation, our analysis starts from the outermost SCC and proceeds inward. When the analysis reaches an inner SCC, it propagates the accumulated path constraints from the outer context and uses them to determine which of the 10 inner-SCC paths are reachable. For each reachable path, the analysis then concatenates the corresponding inner-SCC subsequence with the path of the outer SCC, continuing the exploration.

5.1.2.3 Feature: Field Sensitive

In the following example, the return value of foo() is an alias of the first field of its first argument.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct Point { x: i32, y: i32, } fn foo(p1: &Point) -> &i32 { &p1.y } }

The corresponding MIR code is as follows:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn foo(_1: &Point) -> &i32 { bb0: { _0 = &((*_1).1: i32); return; } } }

The alias analysis result should be (0, 1.1).

5.1.3 Quick Usage Guide

Developers can test the feature using the following command:

cargo rapx -alias

For example, we can apply the mop analysis to the first case, and the result is as follows:

Checking alias_mop_field...

21:50:18|RAP|INFO|: Start analysis with RAP.

21:50:18|RAP|INFO|: Alias found in Some("::boxed::{impl#0}::new"): {(0.0,1)}

21:50:18|RAP|INFO|: Alias found in Some("::foo"): {(0,1.1),(0,1.0)}

When applying the mop analysis to the first case, and the result is as follows:

Checking alias_mop_switch...

21:53:37|RAP|INFO|: Start analysis with RAP.

21:53:37|RAP|INFO|: Alias found in Some("::foo"): {(0,2),(0,1)}

21:53:37|RAP|INFO|: Alias found in Some("::boxed::{impl#0}::new"): {(0.0,1)}

To utilize the analysis results in other analytical features, developers can refer the following example:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let mut alias_analysis = AliasAnalyzer::new(self.tcx); alias_analysis.run(); let result = alias_analysis.get_local_fn_alias(); rap_info!("{}", AAResultMapWrapper(result)); }

The code above performs alias analysis for each function, recording the alias pairs between two arguments or between an argument and the return value.

Key Steps of Our Algorithm

There are three key steps (source code):

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let mut mop_graph = MopGraph::new(self.tcx, def_id); mop_graph.solve_scc(); mop_graph.check(0, &mut self.fn_map); }

- Graph preparation: Construct the control-flow graph for the target function. See the source code.

- SCC shrinkage: Extract the strongly connected components (SCCs) and shrink SCCs of the control-flow graph. See the source code.

- Alias Check: Traversal the control-flow graph and perform alias analysis. See the source code

Reference

The feature is based on our SafeDrop paper, which was published in TOSEM.

@article{cui2023safedrop,

title={SafeDrop: Detecting memory deallocation bugs of rust programs via static data-flow analysis},

author={Mohan Cui, Chengjun Chen, Hui Xu, and Yangfan Zhou},

journal={ACM Transactions on Software Engineering and Methodology},

volume={32},

number={4},

pages={1--21},

year={2023},

publisher={ACM New York, NY, USA}

}